Chinese Dietary Therapy for the Winter Season

Living—and Eating—Seasonally in the Winter

Officially, winter begins here in the Northern Hemisphere on December 21st, 2025. Yet by the looks of it outside my window as I write this, winter is already well underway. Winter is a quiet season here in Northern Vermont. The temperature has warmed slightly today, with a low of 28°F and a high of 38°F, and with a day length of just 8 hours and 52 minutes. We’re getting close to the shortest day of the year.

In the seasonal guide to living—and eating—in the autumn , we introduced the model of the Five Spirits, part of the overall framework of the Five Elements. Within the Five Spirits, the spirit of winter is the Zhì. As we move from autumn into winter, we move from the Pò—the spirit of the corporeal soul—to the Zhì—the spirit of the will.

The Five Spirits Across the Seasons

| Season | Spirit | Emotions (Balanced) | Emotions (Imbalanced) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spring | Hún – Ethereal Soul | Vision, benevolence, initiative, and a sense of life direction. | Anger, suppressed anger, frustration, and resentment. |

| Summer | Shén – Mind/Spirit | Grounded joy, love, connection, and communication. | Frenzy, agitation, overstimulation, and ungrounded, scattered joy. |

| Harvest | Yì – Intellect | Empathy, sympathy, trust, and grounded intention. | Rumination, overthinking, obsession, and worry. |

| Fall | Pò – Corporeal Soul | Letting go, reverence, presence, and an appreciation of life. | Grief, unresolved sorrow, constriction, and holding on. |

| Winter | Zhì – Will | Courage, quiet confidence, ancestral wisdom, and an enduring endurance. | Fear, paralysis, insecurity, and depletion. |

When I was first learning about the Five Spirits, having the spirit of will associated with winter made intuitive sense to me. I understood Zhì as the capacity to endure a long, seasonal winter. I interpreted Zhì as pure motivation—as willpower. Will as a muscle to be flexed when needed. This was a strictly literal understanding, not a metaphorical one.

Today, I relate to the Zhì spirit differently.

For me, Zhì is not my capacity to endure through winter, but my capacity to connect with myself through a rooted knowing of who I am, where I have been, and where I am going. The spirit of Zhì is confidence in myself and in my abilities. It is the knowing that I will be taken care of.

I now relate to the Zhì not as a motivational willpower but as an existential continuity.

If each season—and each spirit expressed within—offers a lesson to guide us, then winter offers the lesson of recollection and connection. Not connection with the other, but with one’s own continuity and lineage. A connection that allows us to become more of who we truly are.

Each fall, I plant garlic. Planting garlic must be timed just right: it needs just enough time to begin to germinate and sprout before going dormant in winter. If garlic misses this narrow window of germination, its taste will be mild. But when the timing is right, the garlic that rests quietly through the winter emerges rich, spicy, and pungent. Garlic needs the winter to become more of who it truly is.

A Framework for Working with Seasonal Foods

Chinese Dietary Therapy in the Autumn and Harvest Season provides an overview of how Chinese Dietary Therapy fits within the Five Branches of Chinese Medicine. If you’re new to this series, start there.

In Chinese Dietary Therapy for the Winter Season, a deeper understanding of diet as a therapeutic framework is introduced. Beginning with Autumn and progressing through the seasons, each seasonal guide builds upon and expands this framework.

In Chinese Dietary Therapy (CDT), foods are not used in place of drugs. Too often, herbs are seen as—or misunderstood as—replacements for or alternatives to prescription medications. This same tendency appears in dietary therapy as well: viewing foods as a 1:1 replacement for a medication (for example, turmeric for its anti-inflammatory properties or garlic for its antiviral properties), or approaching foods through a purely reductionist lens by isolating a single nutrient within them (such as EPA omega fatty acids).

So before focusing on specific foods and seasonal recommendations, it is important to emphasize that within Chinese Dietary Therapy, foods do not exist in isolation, to be plugged in or taken out for a single, targeted purpose. Foods, as with herbs, are not replacements for medications. Instead, CDT is a comprehensive framework that scaffolds an understanding—one often new to readers—of the self, of food, and of disease and pathology. And even when recommending seasonal foods and seasonal dietary patterns, it is imperative to remember that these are not universal or rigid rules; rather, they function as a lens for understanding and a lens for application.

In Chinese Dietary Therapy, Foods and Diets Are Seasonal, Not Static

In Chinese Dietary Therapy, foods and dietary patterns are dynamic rather than fixed, shifting in response to the seasons, to the local geography, to the (changing) climate, and to the stages of life that we move through. What supports one person may not support another, and what supports the body in one winter may not be appropriate in the next. Likewise, what is suitable in winter may be inappropriate in summer, and what is helpful during an acute condition may be harmful when applied to a chronic pattern.

Chinese Dietary Therapy does not rely on universal prescriptions. Instead, foods and diets are applied contextually, based on timing, condition, and the individual’s circumstances and temperament.

Understanding Foods Beyond Nutrition Labels

Moving beyond nutrients, calories, or macronutrients, Chinese Dietary Therapy understands foods first through their energetic qualities. Rather than being evaluated solely through isolated components, foods are assessed through several interrelated factors, which come together to form a schema of understanding. These factors are:

- Temperature (Qì) – Is the food cooling, cold, neutral, warming, or hot?

- Movement of Qì – Does the food’s Qì ascend, descend, disperse, or consolidate?

- Taste – What is the dominant taste of the food? Is it sour, bitter, sweet, spicy/acrid/pungent, salty, or bland?

- Aroma – Is the aroma penetrative, moving, or opening?

- Affinities – Which level or system does the food most strongly influence (Wèi, Yíng, or Yuán)?

Within the model of Chinese Dietary Therapy (as in many systems of Chinese medicine), there are three levels of Qì. The term affinities refers to these three levels within the body: Wèi Qì, Yíng Qì, and Yuán Qì.

Wèi Qì circulates at the surface of the body, supporting external defenses and surface circulation. Yíng Qì, or the Yíng level, is neither superficial nor the deepest level of the body; it relates to the Blood, fluids, and internal nourishment. Yuán Qì, the deepest level, supports constitutional strength, essence, and enduring vitality.

You can think of the Wèi level as the outer surface (and just beyond) of the body. The Yíng level as the muscles, the vessels, the organs, the viscera. And the Yuán level as the deepest: the marrow of the bones, the nucleus of the cells.

Foods have specific affinities for these levels. Understanding the particular affinity of a food becomes essential when using foods to address specific conditions or pathological patterns. Conditions and pathologies affect these specific levels—Wèi, Yíng, and Yuán—and may shift from one level to another over the course of their progression—their etiology. For now, it is sufficient to recognize that these affinities exist.

Applying the Schema to Real Food Choices

Rather than memorizing lists of foods and their associated qualities, the purpose here is to develop a vernacular for learning about foods—one that allows these principles to be applied to foods that are local, seasonal, and accessible. Equally important is how a food is prepared—and how that preparation must shift seasonally.

Processing methods such as cooking, stewing, roasting, fermenting, or juicing can significantly alter a food’s temperature and action. This principle applies not only to foods, but to herbs as well.

Take a raw Granny Smith apple as an example:

- Temperature (Qì) – Cooling.

- Movement of Qì – Dispersing and gently descending.

- Taste – Sour and sweet.

- Aroma – Light and mildly opening.

- Affinities – Primarily Wèi Qì.

By applying the schema to a raw Granny Smith apple, we can see how a single food may or may not be appropriate within a given season or pattern. A raw apple is generally inappropriate for a winter diet (though a baked apple may be appropriate), yet may still be useful even in winter in patterns of acute heat or excess affecting the Wèi level.

Linking Food Choices to the Etiology of Disease

In introducing food affinities above, the etiology of illness was briefly mentioned. Etiology refers both to the origin of an illness—where it originates from—and to its progression over time, including the level at which it is currently expressed in the body.

In Chinese Dietary Therapy, food choices are informed not only by season, but also by etiology. Within this framework, illness may arise from several broad sources, each associated with a different level of Qì.

- External climatic influences (Wèi level) – Cold, wind, or damp producing acute, surface-level expressions.

- Internal emotional patterns (Yíng level) – Prolonged stress or emotional constraint disrupting Blood and fluids.

- Constitutional or inherited factors (Yuán level) – Long-standing patterns shaping development, longevity, and resilience.

At the level of seasonal eating—Spring, Summer, Harvest, Fall, and Winter—Chinese Dietary Therapy does not require a detailed understanding of disease pathology or the specific affinities of individual foods.

Chinese Dietary Therapy and Seasonal Eating in the Winter

Winter and Preservation

As we move from the abundance of harvest and fall into winter, the diet shifts from consolidation toward preservation. Winter is the season most closely aligned with Yuán Qì—our deepest reserves of Qì—and is associated with storage at the deepest levels of the body. Winter eating does not aim to build Yuán Qì directly, but to protect it by minimizing unnecessary expenditure. Where autumn gathers and organizes, winter safeguards and maintains.

Winter is a season of dormancy and recollection. The pause of winter allows what has been stored to mature and transform, just as garlic planted in the fall develops pungency through the winter months. In this way, winter supports continuity—maintaining what has been cultivated and carried forward. This is the lesson of winter and the quality associated with the Zhì spirit.

Seasonal eating in the winter reflects an inward, conserving movement. Foods selected during this time are generally warming, nourishing, and sustaining, rather than dispersing or stimulating, as is more appropriate in the warmer months. Where a raw apple might be suitable in summer, in winter the same apple is baked and combined with warming spices—consolidating its sugars and moderating its dispersing quality while supporting digestion and internal warmth.

In winter, meals are typically built around slow-cooked soups, stews, and broths. Cooking methods favor longer preparation and moist heat, which support digestion and help conserve Qì by reducing the body’s need to expend energy on transformation—on digestion and assimilation.

Energetically, winter is associated with stillness, conservation, and storage, and this orientation is reflected in dietary guidance. It is a season oriented toward maintaining what has already been cultivated rather than initiating change or expansion. Winter eating emphasizes simplicity and consistency, supporting the body through colder temperatures, reduced daylight, and naturally lower levels of activity. Rather than pushing outward, the diet mirrors the season’s inward movement—conserving resources, supporting digestion, and preserving reserves to be carried forward into the renewal of spring.

Pathological Tendencies of Winter

Each season carries with it characteristic pathological tendencies, shaped by climate, movement of Qì, and the body’s relationship to its environment. One of the primary functions of seasonal eating in Chinese Dietary Therapy is not to treat disease directly, but to counterbalance these seasonal tendencies before they consolidate into pathology.

In winter, pathology most often arises through depletion rather than excess. This depletion is not caused by deficiency alone, but by overexertion, excess stimulation, misaligned dietary choices, or cooking methods that work against the season’s inward and conserving nature. For many of us in Western societies, continual activity, overstimulation, and insufficient rest erode our reserves over time, leading to overwork, burnout, and premature aging—patterns of Yīn deficient Heat and Jīng (Essence) Deficiency. For this reason, winter dietary guidance cannot be separated from lifestyle considerations; both are oriented toward conservation and the protection of deeper reserves.

Common Pathological Tendencies of Winter

- Cold – In winter, the primary climatic factor is cold. Cold slows movement and constrains circulation, leading to cold extremities, stiffness, reduced digestive capacity, and a tendency toward contraction when not appropriately counterbalanced through diet and lifestyle.

- Weak Kidney (KI) Qì – Winter is associated with the Kidneys and Yuán Qì (long-term reserves). When diet and lifestyle is not adjusted for the winter, Kidney Qì may become weakened, leading to fatigue, loss of vitality, poor recovery, and an overall feeling of being just worn out.

- Depletion through overexertion – Excessive activity, stimulation, or continual outward engagement through all seasons, and specifically in winter, exhausts stored energy. When expectations and demands (internal and external) remain high during a season that calls for us to rest and to move inward, depletion deepens and worsens over time.

The objective of seasonal eating in winter is to address these pathological tendencies indirectly— by supporting digestion, conserving energy, maintaining internal warmth, and aligning dietary nourishment with the season’s inward, storing movement of Qì.

The Five Elements of Winter In Chinese Dietary Therapy

Chinese Dietary Therapy and Seasonal Eating For the Five Seasons

| Season | Element | Color | Zàng-Fǔ Organs | Spirit | Taste | Climatic Factor | Elemental Foods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Winter | Water | Dark | Kidneys (KI), Urinary Bladder (UB) | Zhì – Will | Salty | Cold | Seeds, legumes, aquatic foods |

| Chinese Dietary Therapy for the Autumn and Harvest Season for a mapping of all the seasons together. | |||||||

Winter and the Five Elements

- Winter is the season of storage – Qì is conserved and held at the deepest level of the body (the Yuán level), emphasizing preservation, safeguarding, and continuity.

- Winter is the energetic season of stillness and maintenance – As seeds (or garlic bulbs) lie dormant beneath the soil through the cold months, we conserve resources and protect our reserves, maintaining and preparing for renewal in spring.

The Element of Winter

- Water – Governing storage and depth, Water is the elemental expression of winter: inward movement, conservation, and the safeguarding of essential reserves at the deepest levels of the body.

The Color of Winter

- Dark / Black – The color of winter, linked to the Kidneys (KI) and the element Water.

- In Chinese Dietary Therapy – Dark foods are emphasized in winter to support storage, conservation, and the Kidneys (KI). These foods are associated with depth and continuity and are used to help maintain reserves through the colder months. Examples include black beans, black sesame seeds, seaweeds, and other dark, mineral-rich foods.

- Dark / Black – The color of winter reflects depth, storage, and continuity. Through diet, darker foods are emphasized in winter for their association with inward movement, conservation, and the maintenance of internal reserves (Jīng and Yuán Qì).

The Zàng-Fǔ Organs of Winter

- Kidneys (KI) and Urinary Bladder (UB) – Are the paired Zàng-Fǔ organs of winter.

- The Kidneys (KI) – Govern storage, essence (Jīng), vitality, and longevity.

- The Urinary Bladder (UB) – Governs separation and excretion, supporting the regulation of fluids.

- As paired Zàng-Fǔ organs – The Kidneys (KI) and Urinary Bladder (UB) regulate storage and release at the deepest level of the body, supporting conservation, continuity, and the maintenance of internal reserves through the winter season.

The Five Element Spirit of Winter

- The Zhì (Will) – The Spirit of Winter; the Spirit of Water. Of the Five Spirits, the Zhì governs resolve, continuity, and the capacity to sustain oneself through time. It is associated with instinctual knowing, ancestral wisdom, and the maintenance of life force through periods of stillness and uncertainty.

- Fear – The associated emotion of the Zhì is fear. When balanced, fear transforms into quiet confidence, wisdom, and trust in one’s own continuity. The work of winter is not to eliminate fear, but to hold it appropriately—allowing it to inform caution and discernment without leading to paralysis or depletion.

- Continuity – Supporting the Zhì in winter means nourishing the body’s capacity to conserve, endure, and remain connected to its deeper reserves. Rather than striving or forcing, winter calls for maintaining what has been stored, trusting in inner resources, and sustaining oneself through consistency, simplicity, and preservation.

Taste and Climatic Factor of Winter

- Taste: Salty – The salty taste supports inward movement, softening, and consolidation. In winter, salty foods are associated with the Kidneys (KI) and support storage, regulation of fluids, and the preservation of internal reserves.

- Climatic Factor: Cold – Cold is the primary environmental challenge of winter, constraining movement, slowing circulation, and burdening digestion—all of which can be counterbalanced through diet and lifestyle.

The Elemental Foods of Winter (Expanded Below)

- Seeds – Small, dense, and highly concentrated foods associated with the Kidneys (KI) and Jīng, reflecting storage and conservation.

- Legumes – Form a bridge between Earth and Water, making them particularly relevant in winter when Kidney (KI) support is emphasized without overtaxing digestion.

- Aquatic Foods – Directly reflect the Water element and Kidney (KI) function. Aquatic foods support fluid regulation, mineral storage, and depth, aligning with the Zhì and the maintenance of pre- and postnatal Yuán Qì.

The Cooking Methods of Winter

Different methods of cooking—such as simmering, stewing, and slow cooking—fundamentally change the nature and action of foods. This is also true in herbalism, where the processing of an herb will fundamentally change the nature of that herb.

In Chinese Dietary Therapy, how food is prepared is considered nearly as influential as the food itself, particularly in winter, when conservation, storage, and the protection of internal resources are paramount.

- Emphasize slow cooking and moist heat – Winter diets should favor longer cooking methods with steady, moist heat. This includes simmering, stewing, and preparing broths—all of which are central to winter eating. These methods warm the interior, conserve Qì, and reduce digestive strain. Slow cooking transforms dense, stored foods—such as roots, legumes, meats, and preserved ingredients—into forms the body can digest and assimilate with ease. Examples include soups, stews, bone broths, meat broths, and long-simmered porridges.

- Avoid excessive raw or cold foods – Raw and cold foods require greater digestive effort and can burden the system during winter, when digestive capacity is naturally reduced and consolidation is emphasized. In winter, foods are generally cooked—often thoroughly—to support digestion and assimilation. Cold, raw, or draining foods should be balanced through cooking (such as in soups or stews) and by combining warming ingredients.

The emphasis here is to cook foods in ways that consolidate their nutritional value while making them easier to digest. Soups and stews conserve the inherent moisture of foods while minimizing digestive demand. Raw, fried, and baked foods are typically minimized or avoided in winter dietary patterns.

Winter Food Categories and Their Therapeutic Properties

Seeds and Seed Fats

An Elemental Winter Food

- Organ affinity – Kidneys (KI)

- Qì level – Yuán Qì

Seasonal Alignment: Seeds are among the most direct dietary expressions of storage and continuity. Their dense, concentrated nature mirrors Essence (Jīng) and supports the maintenance of deep reserves when used sparingly and intentionally.

Examples: Black sesame seeds, pumpkin seeds, sunflower seeds, seed oils and pastes.

Legumes

An Elemental Winter Food

- Organ affinity – Spleen (SP) and Kidneys (KI)

- Qì level – Yíng Qì, indirectly protecting Yuán Qì

Seasonal Alignment: Legumes form a bridge between Earth and Water, making them especially relevant in winter. When thoroughly cooked, they provide steady nourishment without excessive stimulation, supporting conservation while protecting digestion.

Examples: Black beans, adzuki beans, kidney beans, lentils.

Aquatic and Mineral-Rich Foods

An Elemental Winter Food

- Organ affinity – Kidneys (KI), Urinary Bladder (UB)

- Qì level – Yíng Qì with anchoring support to Yuán Qì

Seasonal Alignment: Foods originating from water directly reflect the Water element. Their mineral-rich and salty qualities support fluid regulation, depth, and inward movement in winter.

Examples: Seaweeds, fish, shellfish, aquatic vegetables.

Fermented, Pickled, and Dried (Preserved) Foods

A Supportive Winter Food

- Organ affinity – Spleen (SP), Stomach (ST)

- Qì level – Yíng Qì, protecting Wèi Qì

Seasonal Alignment: Winter emphasizes preservation over freshness. Fermented, pickled, and dried foods reflect winter’s emphasis on consolidation and storage. These foods align with the post-harvest reality of winter while supporting digestion, mineral retention, and internal warmth.

Examples: Fermented vegetables, miso, tempeh, pickled roots, dried mushrooms.

Animal Products and Fats

A Supportive Winter Food

- Organ affinity – Kidneys (KI), supportive to Spleen (SP)

- Qì level – Primarily Yuán Qì, with secondary support to Yíng Qì

Seasonal Alignment: Animal products and fats support insulation, depth, and conservation in winter. They reduce the energetic cost of maintaining warmth and provide dense nourishment that protects deeper reserves rather than stimulating outward movement. Their use is contextual and moderate.

Examples: Pork, poultry, eggs, animal fats, bone broths, meat broths.

Grains

A Supportive Winter Food

- Organ affinity – Spleen (SP)

- Qì level – Yíng Qì, indirectly conserving Yuán Qì

Seasonal Alignment: Grains play a supportive role in winter by stabilizing digestion and preventing unnecessary draw on deeper reserves. They are most appropriate when prepared with long cooking times and moist heat.

Examples: Rice congee, millet porridge, oats, barley (thoroughly cooked).

Cooked Root Vegetables

A Supportive Winter Food

- Organ affinity – Spleen (SP), Kidneys (KI)

- Qì level – Yíng Qì

Seasonal Alignment: Roots support grounding, stability, and nourishment in winter, particularly when thoroughly cooked. Their downward, consolidating nature aligns with winter’s inward movement and complements soups and stews.

Examples: Sweet potatoes, yams, taro, turnips, winter squash.

A Day of Seasonal Eating in the Winter

The following sample day reflects the core principles of winter eating in Chinese Dietary Therapy. Meals are simple, warming, and repeatable, emphasizing ease of digestion, conservation of Qì, and protection of deeper reserves rather than variety or stimulation.

Guiding Principles of Winter Eating

- Choose foods that are local, seasonal, and appropriately stored or preserved – addressing cold tendencies and limited food availability.

- Prioritize conservation over stimulation – eating in winter should emphasize preserving energy and supporting digestion rather than novelty, variety, or sensory excess.

- Eat a narrower range of foods – because consistency and simplicity support the conservation of Qì, Blood, and deeper reserves (Yuán Qì).

- Reduce energetic expenditure through food choices and preparation – emphasizing food choices and cooking methods that allow nourishment with minimal digestive effort.

- Favor slow cooking and moist heat – soups, stews, broths, and porridges support warmth, digestion, and align with winter’s inward, storing movement.

- Avoid excessive raw, cold, and fried foods – which increase digestive demand and undermine the conserving and storage-oriented nature of winter eating.

Morning Breakfast

Morning is when Wèi Qì begins to rise, but in winter digestion is more easily taxed. Breakfast emphasizes warmth, ease of digestion, and conservation rather than stimulation.

- Warm congee – A base of white or brown rice cooked long and slow with ample water.

- Add legumes – Black beans or adzuki beans to support nourishment and conservation without burdening digestion.

- Add cooked root vegetables – Sweet potato or taro, thoroughly cooked to support grounding and ease of assimilation.

- Top with seeds or seed fats – Black sesame seeds or a small amount of sesame paste to support storage and continuity.

- Optional – A small amount of ginger to gently support warmth, used sparingly.

Mid-Morning Snack

Winter eating does not emphasize frequent snacking. If nourishment is needed, it remains simple and warming.

- Warm water, light broth, or leftover congee – Avoid cold beverages or raw foods.

Midday Lunch

Lunch is the main meal of the day in winter, as midday remains the most appropriate time for the heartiest meal, when digestive capacity is strongest.

- Slow-cooked soup or stew –

- Base – Grains and legumes (rice, millet, lentils, black beans).

- Add cooked root vegetables – Sweet potato, yam, taro, or winter squash.

- Aquatic or mineral-rich element – Seaweed, or a small portion of fish if not vegetarian.

- Season lightly – Simple seasonings; avoid excessive spice or stimulation.

- Vegetarian emphasis – Legumes, grains, seeds, and vegetables form the core.

- Vegan option – Include sesame oil or other fats in moderation.

Mid-Afternoon Snack

Afternoon nourishment in winter is modest and optional, intended to maintain steadiness—often described as blood sugar—rather than to stimulate or elevate energy.

- Small portion of seeds or seed fats – Black sesame paste or a few walnuts, used sparingly.

- Warm tea or broth – Avoid cold or iced beverages.

Evening Dinner

As activity decreases, dinner emphasizes warmth, ease of digestion, and consolidation rather than heaviness.

- Soup- or broth-based meal –

- Grains, legumes, and thoroughly cooked vegetables.

- Add winter vegetables – pumpkin, squash, or root vegetables.

- Minimal seasoning – keep flavors simple and grounding.

- Avoid raw foods – Favor cooked preparations only.

Before Bed – Supporting Stillness and Conservation

Evening nourishment anchors the body and supports continuity through the night.

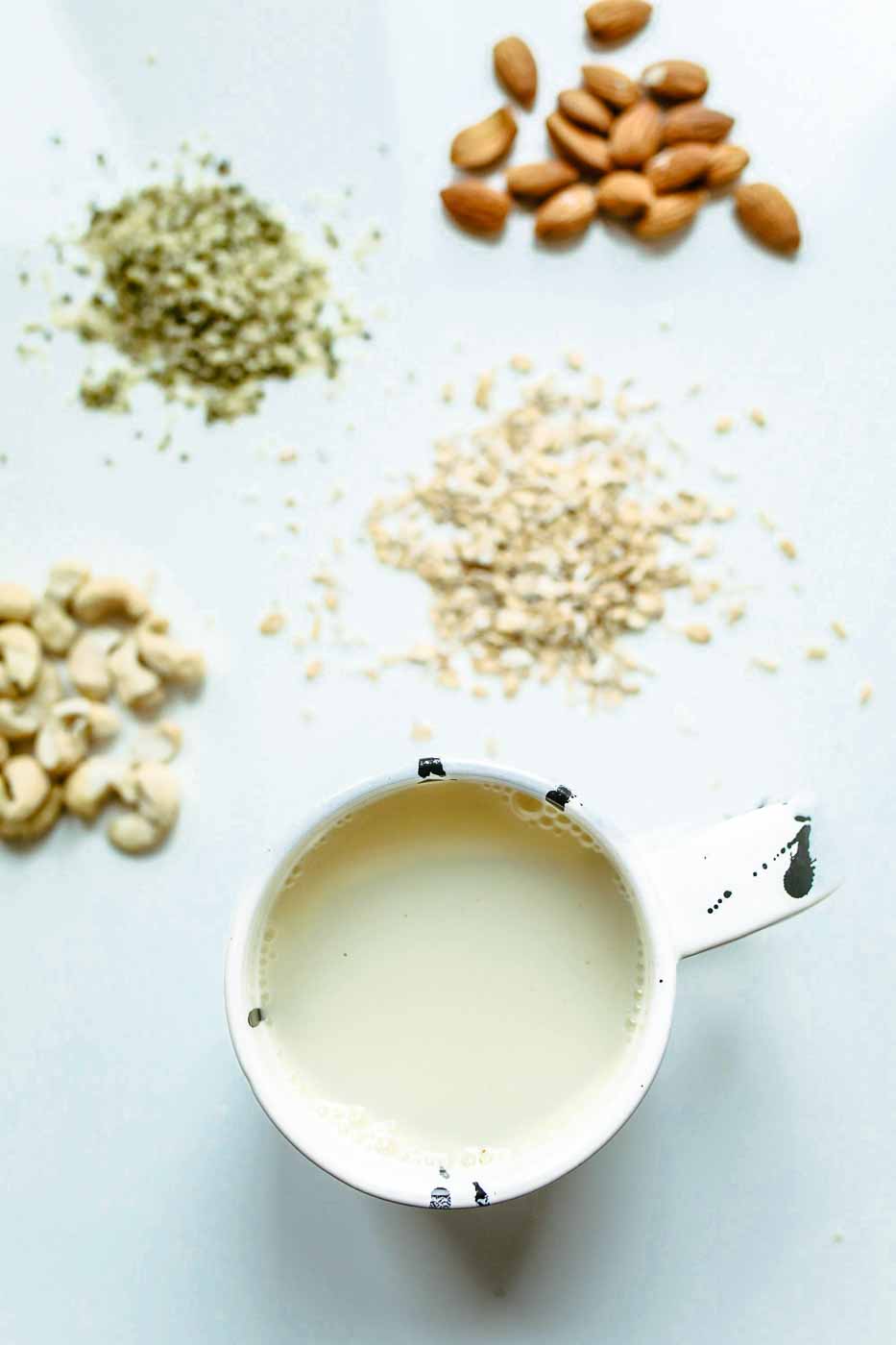

- Warm seed or nut milk – Sesame, almond, or walnut milk, lightly prepared. See our guide to making nut milks in Chinese Dietary Therapy for the Autumn and Harvest Season .

- Optional – A small amount of honey or date syrup, if appropriate.

An Acknowledgment of Citation, Tradition, and Lineage

This document—as with the entire series on seasonal eating—is compiled from class notes taken during the Chinese Dietary Therapy program (2018–2019), taught by Jeffrey C. Yuen —88th-generation Daoist priest of the Jade Purity School, Laozi sect, and 26th-generation priest of the Complete Reality School, Dragon Gate sect.

Site Disclaimers

General Guidence

The content on this site is provided for educational and informational purposes only and should not be construed as medical advice. Always consult a qualified healthcare provider before making changes to your diet, lifestyle, or health regimen, particularly if you are pregnant or nursing, under the age of 18, managing allergies or known sensitivities, or living with any medical conditions.

At RAW Forest Foods, your safety is our priority. Please note that our products are dietary supplements, not medications. The following disclaimer applies:

* These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. These products are not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.

Ingredient Transparency and Allergen Awareness

We are committed to providing transparent ingredient information to help you make informed decisions. If you have or suspect you have allergies to any of our ingredients, we strongly advise against using our products, as allergic reactions can be severe.

Interaction with Medications

If you are taking any medications, consult with your healthcare provider before using supplements. Certain supplements may interact with medications, potentially altering their effectiveness or causing unwanted effects.

For more details, please review our full Terms and Conditions.